Story by: James Chater

Nickel has figured prominently in metallurgy news of late because of its importance to the electric vehicle industry and to the battery storage of renewable energy. But is it all it is hyped up to be? The answer, looking at today’s global markets and the need to develop the renewable and recyclable economy, is a resounding yes.

Introduction

“Jack of all trades, and master of none”, goes an old English saying. However, when it comes to nickel, only the first half applies, given its presence in a number of technically advanced, decidedly smart applications. The already buoyant demand for nickel is likely to soar even higher once the world economy starts to recover from the ravages of Covid. Stainless steel production is already recovering from the 2019 slump, and both the USA and the EU have unveiled stimulus packages that – in the case of the USA at least – foresees infrastructure works that require a lot of stainless steel, nickel’s main application.

The battery effect

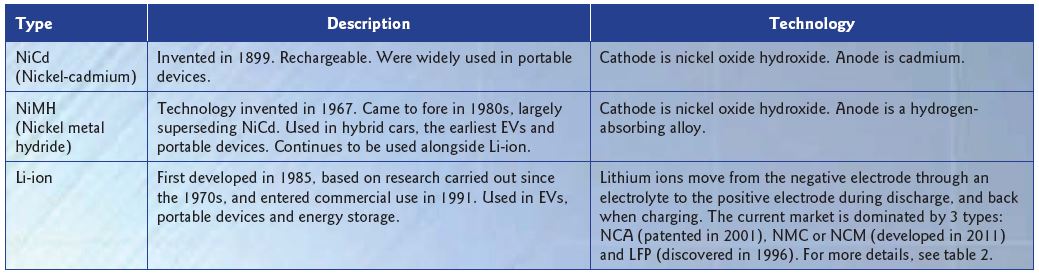

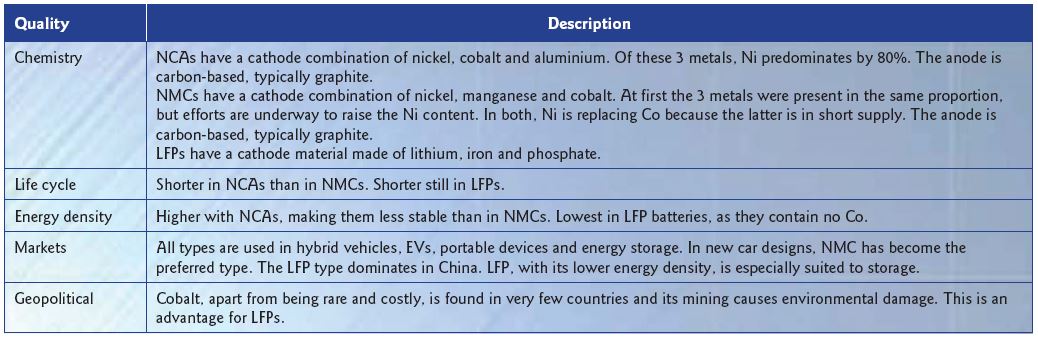

A lot of the buoyancy in the nickel price is attributed to soaring demand from rechargeable batteries. For quite a few years already, nickel has been used in the Li-ion batteries used in portable devices (Tables 1 and 2). There is increased demand for batteries in electric vehicles (EVs) and from storage of power, especially wind, solar or hydrogen. Whether these markets are already large enough to affect nickel prices is hard to know.

However, if at present batteries still represent only a limited market, this is changing extremely rapidly. The demand for nickel in EV batteries is expected to rise ten-fold between 2018 and 2025 (2), and by 2029 demand from battery applications may well outstrip that from stainless steel (3). Moreover, manufacturers are reducing the cobalt content of cathodes and replacing it with the more easily obtainable nickel. This is the case in the new NCM-811 (so-called because the cathode is eight parts of Ni to one each of Co and Mn), a single-crystal battery only 1 to 3 microns wide.

The dilemma for battery makers is that nickel improves energy density but can make batteries unstable and liable to overheat. Can lithium-ion batteries be made more stable without losing their energy density? Or will the zero-nickel LFP type be developed to become more energy-dense, to the point that they will rival lithium-ion? These questions have important implications for the nickel industry in the long term.

Nickel prices

Nickel prices are volatile, both reflecting economic uncertainty and sowing it in the minds of end-users eager for more predictable prices. Since late 2019 prices soared, plunged, soared again and since declined in a range between USD 11,000 and 19,000 per tonne. Recent price movements have been especially yoyo-like: the years 2018-9 saw a rise from 11,000 in November to a peak of 19,690 in September, followed by a sharp decline, no doubt aggravated if not caused by Covid, back down to 11,000 (March 2020), rising again to 19,690 (February 2021) and descending to its current level of just above 16,000 (1).

The 3D effect

“I make, therefore I AM” would be a good slogan for additive manufacturing (AM), also known as 3D printing. Apart from the stainless steel and rechargeable battery markets, it is probably the most important driver of the nickel industry right now. New nickel alloys are appearing that are tailor-made to take advantage of the higher quality and greater strength of which 3D printing is capable while avoiding the danger of cracking. EOS is offering a number of Ni alloys in powdered form for 3D printing. UC Santa Barbara and Oak Ridge National Laboratory are collaborating to develop a class of high-strength, defect-resistant 3D-printable nickel-based superalloys containing approximately equal parts of Co and Ni, along with Al, Cr, Ta and W. 3D Systems is collaborating with Huntington Ingalls Industries’ shipbuilding division to develop 3D-printable copper-nickel alloys for powder bed fusion AM. They hope to make castings, valves, housings and brackets with a 75% reduction in lead times.

Other applications

Even without the EV revolution, nickel finds many other uses both in this and on other worlds. The following is a partial list:

Severely corrosive environments Sandvik’s new Sanicro® 35 superaustenitic (with 35% Ni) bridges the gap between standard duplex on the one hand and austenitic grades and nickel alloys on the other. Offered in seamless tube and pipe, it is ideally suited for heat exchangers in severely corrosive environments and, especially, to handle seawater used for cooling or heating. Easy to weld, highly resistant to pitting (PREN = ~52), stress corrosion cracking and crevice corrosion, it can replace 6Mo, alloy 825 or alloy 625.

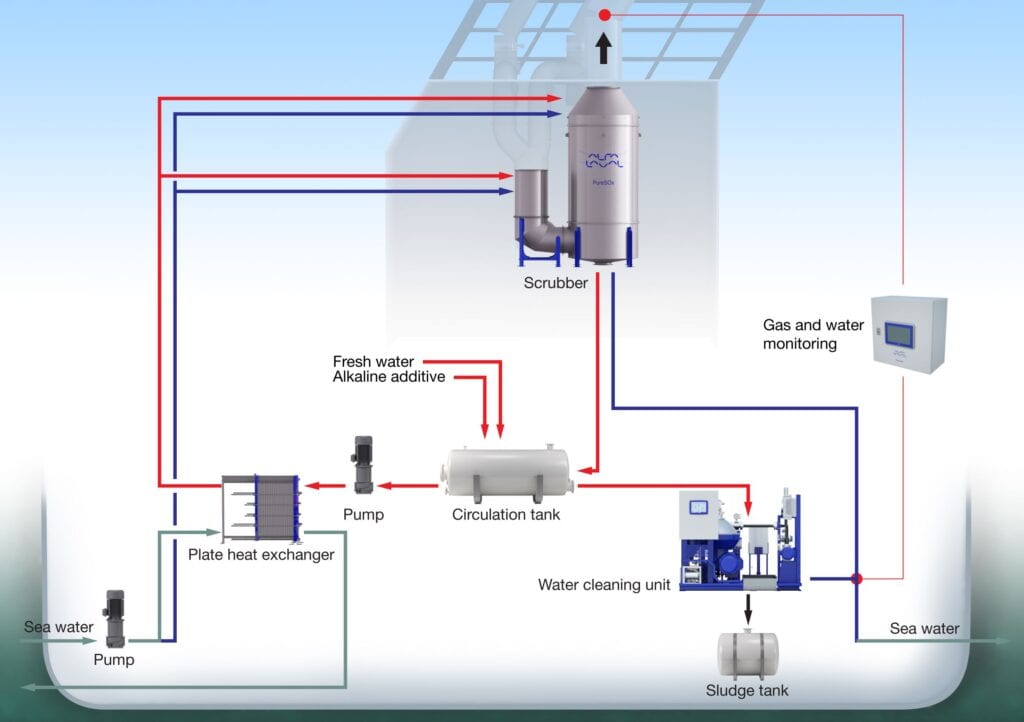

New emissions norms for coal-fired plants and ships require scrubbing (FGD or flue gas desulphurization) systems. In March, Sverdrup Steel announced it was supplying its alloy 31 plates for a Polish customer.

Ideal for FGD systems with a phosphoric environment, this alloy is a nickel, chromium, and molybdenum stainless steel with nitrogen and copper additions. SOx emissions, which contain diesel and sulphur particulates, are strictly controlled in certain of the world’s waterways, obliging many ships to install exhaust gas cleaning systems. For the hot acidic chloride solutions inside the scrubber, highly corrosion-resistant nickel alloys are required, such as alloy 31, C-276 or 59. Scrubber systems can be open if the ship is in waters with high alkalinity, which neutralizes the acid discharge; but in areas of low alkalinity, closed-loop systems are necessary.

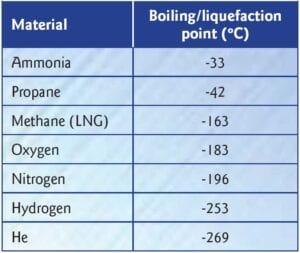

Cryogenic environments Many new industries, especially LNG, LPG and hydrogen, require liquefaction of gases for transportation and storage. In general, the lower the boiling points, the stronger the alloy has to be. Ni-alloyed steels of varying strengths are used to handle ammonia, propane, CO2, ethylene and LNG, whereas nitrogen, hydrogen and helium require austenitic stainless steels.

Part of the expense of hydrogen – and therefore one of the obstacles to its wider use – is its low liquefaction point. Ni-containing austenitics are required for handling, and nickel is also used in the catalysts of some new processes which promise to bring down the cost of H electrolysis. (Traditionally, electrolysis has been carried out with platinum or some other inert metal used as a catalyst, so replacing these with nickel is a cost saving.) For example, Pohang University has proposed a way to produce H using Ni as an electrocatalyst. At Stanford University, a process of electrolysis in seawater has been studied, producing H more efficiently by introducing an anode of layered nickel-iron hydroxide on top of nickel sulphide, covering a nickel foam core, to repel corrosive chloride. Chiyoda Corporation has developed the SPERA Hydrogen system, a process for handling H using organic chemical hydride (OCH) to store and transport H as liquid methylcyclohexane (MCH) at ambient temperatures. Here too, Ni is used as a catalyst.

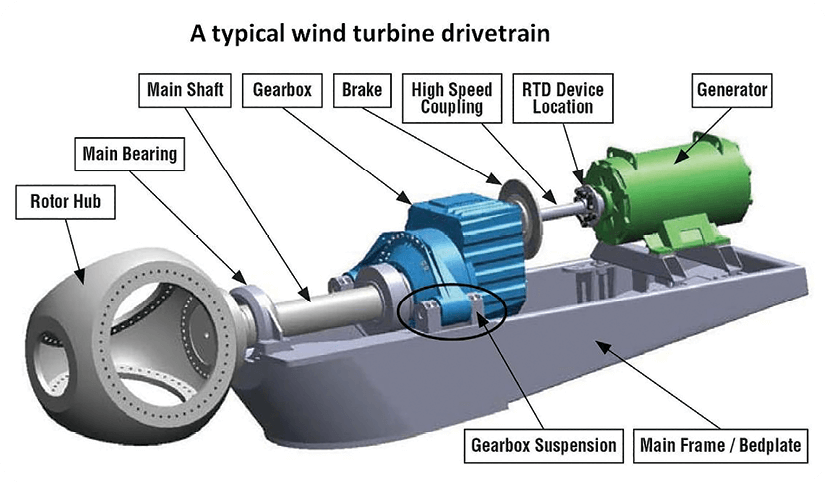

Wind power Several forms of renewable energy require nickel. In wind power, high strength and ductility are required in certain applications, for which nickel-steel alloys are ideal. For instance, the gearbox requires heat-treatable carburizing steel 18CrNiMo7-6 and austempered ductile iron (ADI), to which Ni, Mo and Cu are added. Heat-treatable CrNiMo steels are used in the generator, the main shaft, screws and studs.

Space Nickel’s use in jet engines is well known, but perhaps even more remarkable is the rapid proliferation of space exploration missions, all requiring vehicles that make use of Ni in various ways. Ni-Cu (Monel) alloys, which resist both burning in oxygen and subzero temperatures, can be found in tubes, pipes, rods, and wire for various applications, and in the turbo-pumps for the oxidizer side of the oxygen-rich liquefied-fuel rocket engines such as the Blue Origin BE-4. Blue Origin 3D-printed complex parts for its Ox Boost Pump. The housing is in aluminium and the hydraulic turbine, nozzles and rotors are all in Ni-Cu. The most ambitious space mission of our day is the SpaceX project to transport people to Mars.

The SpaceX Starship Raptor rocket engine is one of the first to be powered by liquid methane and liquid oxygen and designed to be reused 1,000 times. One of the possible catalysts is nickel. Alloy 718 nickel-chromium alloy is also used in rocket engines and pressure vessels, so they can handle cryogenic liquefied gases for propulsion down to -250 °C. No doubt further missions will throw up more and unexpected opportunities to apply nickel. For example, for its Rover vehicles that explore the surfaces of moons and planets, NASA is developing a wire mesh tyre to replace the rubber or steel previously used, which tend to buckle. It is made of Nitinol, a nickel-titanium

“memory shape” metal that can spring back to its former shape rather than deforming.

Conclusion

Whether beneath, on or above the earth, whether in hot or cold environments, you cannot escape nickel, nor would you want to.

References

(1) https://markets.businessinsider. com/commodities/nickel-price

(2) https://www.statista.com/statistics/967700/global-demand-for-nickel-in-ev-batteries/

(3) https://www.greencarcongress. com/2020/06/20200602-roskill.html

Every week we share a new Featured Story with our Stainless Steel community. Join us and let’s share your Featured Story on Stainless Steel World online and in print.

Featured Story by: James Chater

All images were taken before the COVID-19 pandemic, or in compliance with social distancing.