The Amercentrale solar park, the Netherlands. Photo: RWE.

The challenge of replacing Russian gas with a reliable energy source has prompted steps forward as well as back. Coal is making a comeback, and nuclear fission is being re-assessed; but at the same time the transition towards green energy is accelerating. The war in Ukraine, along with the grim predictions of climate scientists, is driving an energy revolution which can be seen above all in the rapid growth of solar, wind, tidal, and geothermal energy. And let’s not forget hydrogen.

By James Chater

Thirst for electricity

In the US presidential election campaign of 1992, Bill Clinton famously reminded himself: “It’s the economy, stupid!” If we replace the word “economy” with “electricity”, the challenge is clear: it’s all about electricity! The energy transition requires green electricity – much more than is currently being generated. The demand comes from the usual places: homes, electric cars, and industry. It is above all, industry that is tipping the scales right now. Heavy industry is turning away from coal and gas and towards electricity. The steel industry is heading the charge, replacing coal and coke with electricity or hydrogen. (Many steel companies are decarbonising, and SSAB has stated it has produced the world’s first 100% fossil-free steel.) Other industries, such as mining, are following suit.

Green energy worldwide

According to the International Energy Agency, the output of mass-produced clean energy will triple by 2030. The fastest-growing clean energy types are wind and solar, which together represented 12% of electricity generation in 2022, up from 10% in 2021.

Europe remains at the forefront of green developments. Although BP has pared back its green investments, other companies, such as Italy’s Enel and Portugal’s EDP, are forging ahead. The EU, keen to compete with the USA and China, is streamlining approvals for green projects and allowing increased levels of state aid. This is fully supported by Germany, which aims to generate 80% of electricity from renewables by 2030 and install 30 GW of offshore wind capacity by that date.

Offshore wind developments have been approved by Spain, with Iberdrola making vast investments; Portugal’s first offshore wind farm has come onstream at Mina de Orgueirel, and the country is aiming to install 10 GW by 2030. One of Italy’s poorer regions, Sicily, has received an economic shot in the arm thanks to Enel’s doubled-sided solar panel factory near Catania.

Further north, Equinor and SSE Renewables are expanding their wind farm at the Dogger Bank, Denmark is issuing tenders for 9 GW of offshore wind this year, and Norway has opened tenders for two wind parks that will produce about 3 GW. The UK has announced green power auctions worth GBP 205 million.

The USA’s Inflation Reduction Act (2022) introduces measures to cut CO₂ emissions by 40% by 2030. Like the EU, the USA is reforming its regulations to make it easier to develop wind farms. And here, too, the focus is on offshore wind. Equinor and BP plan to expand their Beacon Wind project off New York, while Glennmont Partners is collaborating with GreenGo Energy US to develop over 1 GW of solar and storage projects. Further south, Mexico has inaugurated a giant solar park in its northern desert; Latin American and Caribbean countries account for about 250 solar power projects.

All over the Middle East, solar and wind projects are changing the energy mix in a region that traditionally has a low share of green power. Green capacity jumped an impressive 12.8% in 2022. Saudi Arabia has announced investments of up to USD 266.40 billion. Much of the work is being carried out by Masdar, a UAE-based energy company active in the Middle East, Central Asia, and Africa.

The continent of Africa is facing energy shortages as droughts reduce output from hydro. South Africa, which has experienced blackouts, is introducing legislation to fast-track power projects. Other countries forging ahead with projects include Zimbabwe (where China will build a floating power plant), Morocco, Kenya, Ethiopia, Zambia, and Egypt.

Another state that is catching up in its green energy projects is Australia, where clean energy project approvals have doubled under the current administration. A clean energy plan unveiled last September foresees USD 40 billion to convert coal-fired plants to renewables. In Asia, India has undergone a solar boom that has replaced gas but left coal use largely unaffected. The state will invite bids for 8 GW of wind power annually until 2030. China plans to build a mind-blowing 450 GW of solar and wind power in the Gobi desert.

Innovation

The green energy sector continues to innovate. To avoid consuming too much land that could be used for farming, floating solar power plants have been introduced, and now “agrivoltaics” is being touted as a way to protect crops from excessive global heating. The idea is to grow them under and between PV panels and to allow crops and animals to benefit from the shade and lower temperature. Agrivoltaics is being pioneered in Japan, South Korea, France, and China.

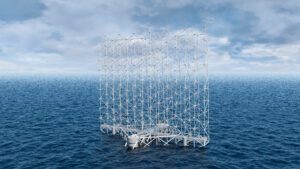

In wind power, a striking innovation is the Windcatcher, an offshore floating turbine with 117 rotors stacked vertically to about 300m. The small blades are more efficient than the large ones, harnessing higher wind speeds.

Wave/tidal power has always lagged behind wind and solar, but new technology suggests this will change. Enel’s wave converter, the PB3 PowerBuoy, and the Orbital O2 in Orkney are two examples. The Orbital O2 is the world’s most powerful tidal stream energy generator. It has been estimated that tidal stream power alone could provide 11% of the UK’s electricity needs. Geothermal, like wave/tidal, has the advantage over wind and solar of providing a steady flow of energy.

It is still undergoing evolution. For example, Vendicorp is working with the University of Queensland to develop new technology with supercritical turbines, and heat exchangers and air-cooled condensers for geothermal, solar thermal and waste heat power generation. CeraPhi and Fraser Well Management are working on a closed-loop system that will use redundant oil & gas wells for heat transfer, permitting power generation from lower temperatures to heat cities and districts.

Overcoming intermittency

How to overcome the fact that the wind does not always blow and the sun does not always shine? One answer is hybrid systems. These generate electricity from two or more sources, usually renewable, using a common connection point. So when the wind blows less hard, and the sunshine grows stronger, as often occurs in summer, one can switch from wind to solar. Such systems are often stand-alone and come with storage or conversion to hydrogen (see below).

Li

There is bad and good news in the storage sector. The main storage technology still involves lithium batteries, which have two disadvantages: they are prone to catch fire, and the West is dependent on China for most of its lithium supply. The other bad news is that storage systems are not developing fast enough to allow energy companies to wean themselves off base-load power sources. Moreover, electric cars compete with power generation for storage batteries. Demand for lithium batteries is expected to increase more than five-fold by 2030. Despite recent projects, such as Masdar’s investment in the UK with USD 1.2 billion, Albemarle’s lithium plant in S. Carolina, and Glencore’s collaboration with Iberdrola, lithium battery storage is unlikely to keep pace with demand.

CO₂

Fortunately, other solutions exist. One, surprisingly enough, involves CO₂! Energy Dome has developed a technology based on a thermodynamic transformation of CO₂ in a closed-loop process, essentially a thermomechanical process. Using excess green energy, CO₂ gas is compressed, stored, and liquefied. When the energy is required, it is evaporated and expanded, driving a turbine. The compressors, turbines and heat exchangers are very similar to what is used in the oil & gas industry.

H

The other solution is the fast-growing industry of green hydrogen. Hydrogen is produced by splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen through electrolysis. This requires an energy source, and when this is green electricity, it means a net reduction in CO₂ emissions. Ørsted’s H2RES project in Denmark is a good example: this wind-to-hydrogen project is situated offshore Denmark. Similar is the NortH2 project in the Netherlands, where hydrogen will be generated from a 3-to-4 MG offshore wind farm. Other projects are being developed in China (the west-to-east H pipeline), France, Portugal, Europe (a pipeline network), Canada, Spain (the BP green H hub), the Americas, and Africa.

Despite the impressive number of projects currently underway, we are still some way off from a hydrogen infrastructure that can function as a backup for intermittent renewables. But give it time.

Labour shortage

Looking for a job and unafraid of heights? A future installing solar panels or wind towers could be just the ticket! The massive investments planned for solar and wind are stretching the available workforce to the limit. Following President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act, the labour shortage is especially acute in the USA. But Europe also faces a shortage of solar installers. BP has recently announced it will hire over 100 employees to install its offshore wind farms.

How stainless steel is used in renewable energy

Wind: In offshore wind installations, corrosion from sea spray is a major concern. Stainless steel is used in applications such as electrical boxes, fasteners, cables, fittings, etc.

Solar: Thermosolar systems apply stainless steel in the form of thin-walled tubes and sheets to facilitate heat transfer in heat exchangers, tubes, water tanks, frames and fasteners. Photovoltaic cells are usually attached to roofs with stainless steel. In concentrated solar power

(CSP), parabolic mirrors use stainless steel, while the pipes that transport the heated medium use nickel alloys.

Geothermal: In this highly acidic environment, duplex grades, nickel alloys and titanium are regularly used in heat exchangers, pipes, pump shafts and valves.

Tidal/wave: stainless steel can resist corrosion from saltwater, biofouling and abrasion.

About this Featured Story

This Featured Story appeared in Stainless Steel World August 2023 magazine. To read many more articles like these on an (almost) monthly basis, subscribe to our magazine (available in print and digital format – SUBSCRIPTIONS TO OUR DIGITAL VERSION ARE NOW FREE.

Every week we share a new Featured Story with our Stainless Steel community. Join us and let’s share your Featured Story on Stainless Steel World online and in print.