Since the Wright Brothers first achieved mechanical flight, humans have worked on perfecting the propellor. Stainless steel grade 431 is a highly suitable material which far outperforms aluminium.

By Srikumar Chakraborty, ex, ASP/SAIL, freelance consultant

The propeller is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades set at a pitch to form a helical spiral that exerts linear thrust upon air or water. Propellers work similarly to how a screw works. For aircraft applications, as the blades rotate, air accelerates over the front surface, causing reduced static pressure ahead of the blade and resulting in forward thrust. This generates aerodynamic force while spin creates a forward direction.

Material of manufacturing

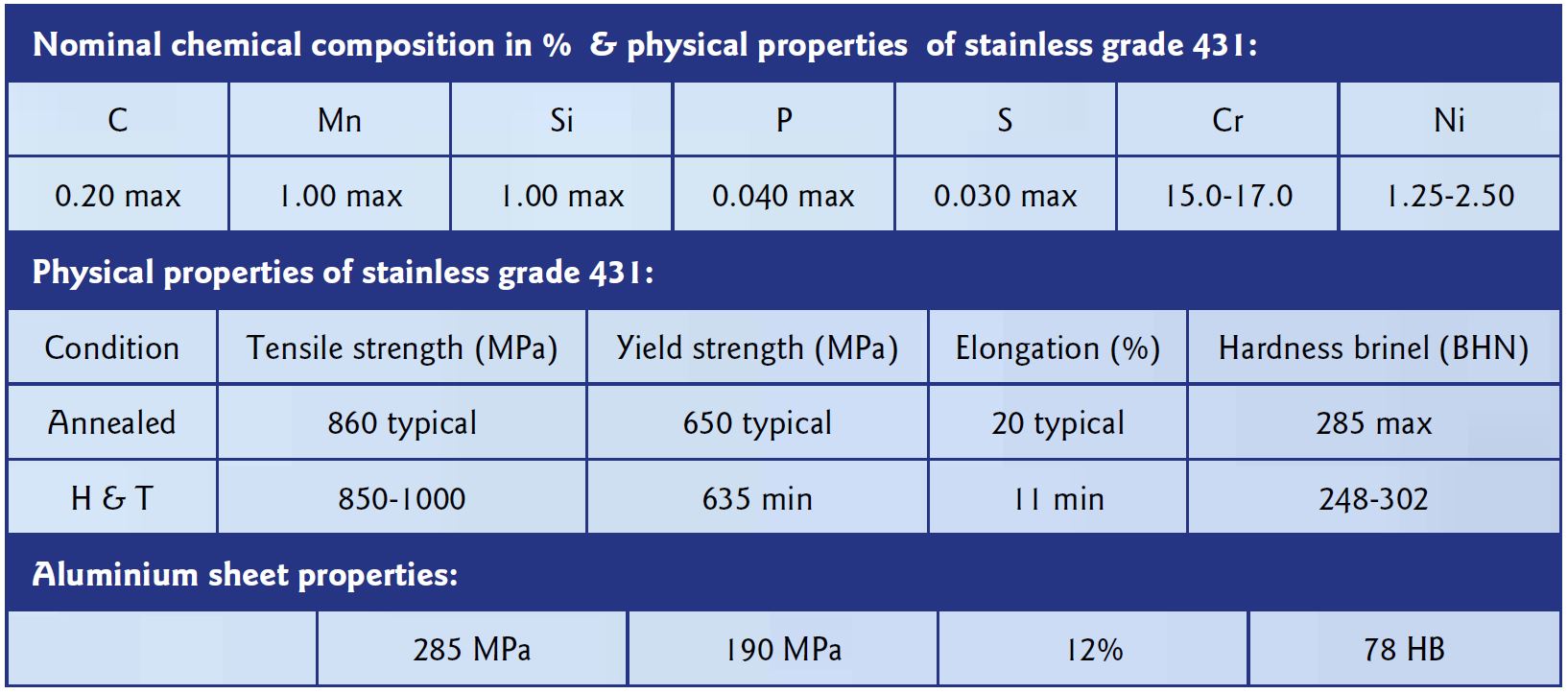

Martensitic stainless steel grade AISI 431 is highly suitable for propellers in the marine, aerospace and automobile industries. This grade offers superior corrosion and heat resistance. In terms of mechanical properties, grade 431 offers five times more stress tolerance than aluminium, meaning that the blades can be significantly thinner. In addition, grade 431 propellers are more durable, with greater tolerances to help reduce drag on the motor, even at very high speeds.

Early history of the propeller

more stress tolerance than aluminium.

The first propellers were derived from a rotating screw design invented by the ancient Greek scientist Archimedes in 200 BC. Ancient civilisations used these to extract water from wells with little effort. Propeller technology advanced rapidly after the Wright Brothers’ breakthrough design in 1903. While the Wrights’ propellers were about 82% efficient, today’s propellers operate at around 90% efficiency.

In the aircraft industry, the first propellers were made from wood and had a fixed pitch, greatly limiting the aircraft’s performance capabilities. However, in 1929, Wallace Turnbull patented his design for a variable pitch propeller, which allowed the pilot to manually adjust the blade pitch and maintain better control over the aircraft’s performance and operational efficiency. Later, constant-speed propellers with a variable pitch that automatically adjusted to maintain a constant rotational speed were developed. Most of today’s high-performance propeller aircraft use constant-speed props because they offer better performance and fuel efficiency. Hartzell Propeller has been at the forefront of aircraft propeller design and manufacturing since the early days of aviation.

Aircraft propellers are often made from aluminium or composite materials and range from two to six blades. However, stainless 431 propellers have successfully and more efficiently replaced these.

Stainless steel 431 vs aluminium

Regarding performance, a stainless steel propeller functions better and more efficiently in terms of cost, quality, superior ductility, maintenance-free and lifecycle cost than aluminium. Produced by cold rolling, thin stainless blades create high-performance propellers with reduced drag and a stiffer, stronger profile that can cut through water or air more efficiently. This drag reduction makes it easier to reach top speed with better fuel efficiency.

Process metallurgy

more stress tolerance than aluminium.

AISI 431 is the most important stainless steel in the martensitic group to manifest an undesirably strong tendency to form delta ferrite (if a ferrite-former such as Cr is high) and/or retained austenite. This is due to the difficulties in the commercial practice of observing the extremely close tolerances necessitated by the chemistry of the steel. As a result, the microstructure may not be uniform from heat to heat, and is too often characterised by excessive amounts of austenite and/or the delta ferrite phase conducive

to embrittlement. These objectionable processing difficulties are perhaps partially responsible for the production of grade 431 not appreciably increasing over the last twenty years. In addition, the high carbon content in 431 renders the alloy challenging to weld or hot work. However, the presence of nickel (austenite former) at the 1.25-2.5 % level counteracts the delta ferrite formation tendency, balancing a desirable structure and workability. Excess nickel can lead to undesirable quantities of retained austenite on cooling from the austenitic condition. It should be mentioned that at elevated temperatures, a completely austenitic structure is desirable for good processing characteristics, particularly forgeability, rollability and weldability. However, the steel should transform at least substantially to martensite upon cooling to about room temperature. To that end, the sum of the percentages of nickel and chromium together should not exceed 21.5% in this grade and preferably should be less than 21.25%. It is essential to carry out standard

tests to get the specified values such as toughness characteristics, including tensile, yield, elongation, reduction in area and Charpy V-notch energy values conducted on steel products. Even for plate products, it is documented that the ability to absorb impact energy is usually significantly higher when measured in the longitudinal direction as opposed to the direction transverse to rolling.

Conclusion

Aluminium propeller blades are thicker than stainless ones and create more drag at top speed. The physical and mechanical properties of AISI 431, e.g. tensile and compressive properties, impact energy and dynamic fracture toughness and exhibit an overall superior performance compared to other metals.

About this Featured Story

This Featured Story appeared in Stainless Steel World October 2023 magazine. To read many more articles like these on an (almost) monthly basis, subscribe to our magazine (available in print and digital format) – SUBSCRIPTIONS TO OUR DIGITAL VERSION ARE NOW FREE.

Every week we share a new Featured Story with our Stainless Steel community. Join us and let’s share your Featured Story on Stainless Steel World online and in print.