For the ramp-up of the hydrogen economy, complex material and tubing solutions are required. In certain applications, seamless stainless steel tubes offer a viable option. In this context, Tim Wallbaum from DMV explains the fundamental mechanisms of hydrogen embrittlement and how the hydrogen resistance of seamless stainless steel tubes can be influenced by their chemical composition.

By Tim Wallbaum, DMV GmbH

Hydrogen embrittlement and key influencing factors

Hydrogen embrittlement is a phenomenon where metallic materials experience a degradation in mechanical properties due to exposure to hydrogen. This effect can significantly weaken properties like tensile strength, elongation at break, reduction in area, fatigue strength, and fracture toughness. Under certain conditions, hydrogen embrittlement can diminish load-bearing capacity or even cause failure at stress levels below the material’s yield or tensile strength. In some cases, failure can occur without any external load, solely from internal stresses1,2.

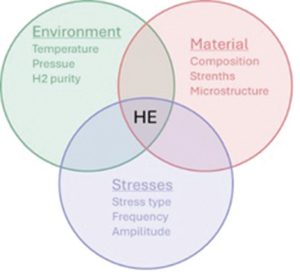

For hydrogen embrittlement to take place, three conditions must converge: sufficient hydrogen concentration, a certain level of applied or residual stress, and a material that is susceptible to embrittlement. Each of these factors is further influenced by conditions such as temperature and pressure, the type of stress (tensile, compressive, static, or dynamic), and material characteristics like safety factors, microstructure, and chemical composition3.

Mechanism of hydrogen diffusion

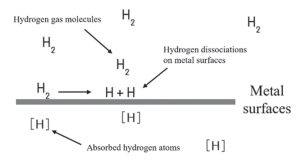

Due to its small atomic size, hydrogen can penetrate the crystal lattice of stainless steel, migrating through interstitial sites between metal atoms. Concentration gradients primarily drive this diffusion process, but it is also influenced by external factors such as pressure and temperature. When stainless steel is exposed to hydrogen gas, molecular hydrogen (H2) dissociates on the metal surface into atomic hydrogen. This dissociation process is facilitated by higher temperatures and surface imperfections, which provide the energy required to break hydrogen-hydrogen bonds. In its atomic form, hydrogen can enter the stainless steel matrix, diffusing through the interstitial spaces within the lattice4.

The rate and extent of hydrogen diffusion are strongly influenced by the microstructure, alloy composition, and environmental conditions of the stainless steel. For instance, austenitic stainless steels, which have a face-centered cubic (FCC) lattice structure, generally offer greater resistance to hydrogen diffusion than ferritic or martensitic stainless steels due to fewer direct diffusion pathways. However, elevated temperatures enhance hydrogen mobility, allowing it to surmount lattice energy barriers more easily. Impurities, dislocations, and grain boundaries in the metal serve as potential traps or pathways for hydrogen atoms, affecting their diffusion behaviour. These sites can lead to localised hydrogen accumulation, which, under certain conditions, may contribute to embrittlement. A thorough understanding of these diffusion mechanisms and influencing factors is crucial for designing stainless steel components that can reliably perform in hydrogen-rich environments where material integrity is paramount.

The theoretical foundations have now been outlined, detailing the prerequisites necessary for hydrogen embrittlement of steel, along with an explanation of the mechanism by how hydrogen enters the material. Building on this, the following illustrates how the hydrogen resistance of austenitic stainless steels can be influenced by their chemical composition, where the so-called nickel equivalent value in particular plays a significant role.

Influence of the nickel equivalent

Nickel equivalent is a measure of the amount of nickel and nickel-like elements required to stabilise the austenitic phase in a stainless steel. This phase is known for its high ductility and toughness, properties that are particularly important in preventing hydrogen embrittlement. Nickel equivalent, defined by a combination of alloying elements such as nickel (Ni), chromium (Cr), manganese (Mn) and others. The nickel equivalent has a decisive influence on the stability of the austenitic microstructure and thus on the ability of the material to withstand the damaging effects of hydrogen. Several empirical formulas have been established for its calculation. The most commonly used formulas in the hydrogen industry are Schäeffler’s formula (1) and Sanga’s formula (2), which, in contrast to formula 1, includes several alloying elements in the calculation. It is possible that the customer specifies a minimum value for the nickel equivalent, on the basis of which a material selection can be made5.

(1) Nieq = Ni + 30C + 0.5Mn

(2) Nieq = Ni + 0.72Cr + 0.88Mo + 1.11 Mn – 0.27Si + 0.53Cu + 12.93C + 7.55N

In the Table 1, the DMV 316L and DMV 316LMoS materials were calculated using formulas (1) and (2). As the individual compositions of the alloying elements of the DMV materials each consist of a minimum and a maximum value, this was also taken into account in the calculation. As the results in the table show, the values differ greatly depending on the calculation formula, and the minimum and maximum values also show differences that need to be considered. Therefore, if a material is to be selected for use in a hydrogen application based on the size of the nickel equivalent, the formula to be used must also be discussed. In addition, it should be determined whether the minimum, maximum or average values of the alloy element proportions should be used for the calculation.

Slow strain rate tests (SSRT) are generally used to prove the influence of the nickel equivalent on the hydrogen resistance of stainless steel. SSTR tests are tensile tests with a very slow strain rate, allowing the hydrogen resistance of materials, especially austenitic stainless steels, to be evaluated. A sample is loaded at a very low strain rate under the influence of hydrogen.

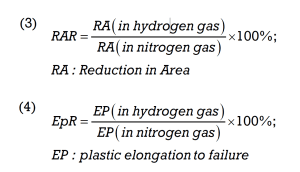

This slow deformation process allows the hydrogen to diffuse into the material and make the interactions with microstructural weak points, such as grain boundaries and dislocations, visible. The results of the SSRT test are then compared with a reference test in an inert gas such as nitrogen. A loss of ductility, reduced elongation at break or a brittle fracture are indicators of increased susceptibility to hydrogen embrittlement. The SSRT method thus allows a precise assessment of hydrogen resistance. The effects of hydrogen embrittlement are quantified using formula (3), the calculation of the relative reduction in area ratio (RAR), or formula (4), the plastic elongation to failure ratio (EPR).

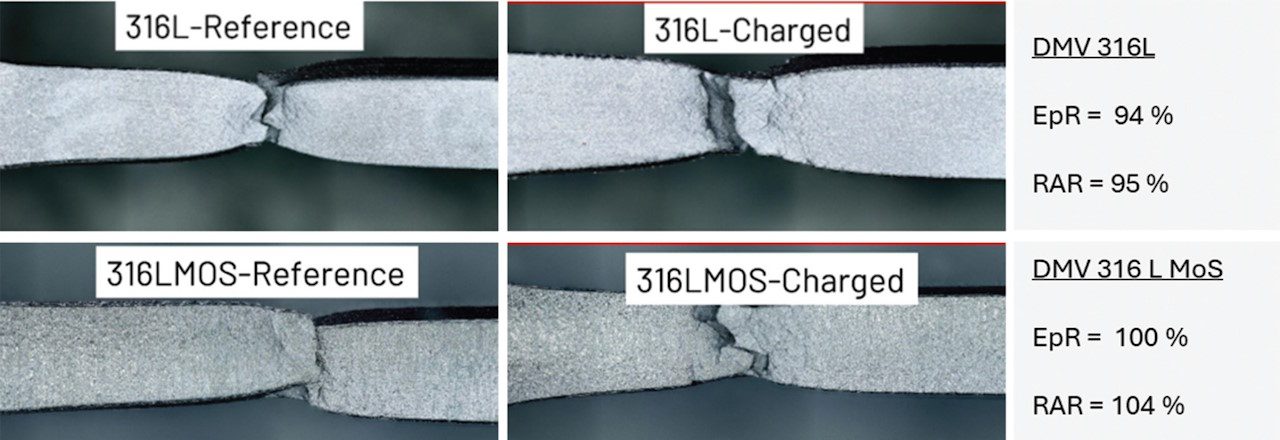

For SSRT tests according to NACE TM0198, the DMV 316L and DMV 316LMoS samples were manufactured from cold-finished tubes in our Costa Volpino facility. The individual samples were pre-loaded with hydrogen and tested at a pressure of 150 bar and room temperature in the autoclaves of the SSRT machine. As can be seen from the data in Figure 3, the material DMV 316L shows a slight hydrogen embrittlement, whereas the DMV 316LMoS shows no hydrogen embrittlement.

Table 1. Calculation of the nickel equivalents for DMV 316 L and DMV 316 LMoS

| Ni | Cr | Mo | Mn | Si | Cu | C | N | Nieq (2) | Nieq (1) | |

| DMV 316L | ||||||||||

| Min | 11 | 16.5 | 2 | 1 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0.04 | 26 | 11.5 |

| Max | 12 | 17.5 | 2.4 | 2 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 29.95 | 13.9 |

| Average | 11.5 | 17 | 2.2 | 1.5 | 0.45 | 0.2 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 27.97 | 12.7 |

| DMV 316LMoS | ||||||||||

| Min | 13 | 17 | 2.5 | 1 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0.04 | 28.8 | 13.5 |

| Max | 14 | 18 | 2.75 | 2 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 32.61 | 15.9 |

| Average | 13.5 | 17.5 | 2.63 | 1.5 | 0.45 | 0.2 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 30.71 | 14.7 |

Discussion

Hydrogen embrittlement is a complex phenomenon that can significantly degrade a material’s mechanical properties, such as the ductility of steel. In extreme cases, embrittlement can even lead to material failure without the influence of external load. The occurrence and severity of hydrogen embrittlement are determined by a combination of factors: hydrogen application conditions (such as pressure and temperature), applied stresses, and material properties, including chemical composition and microstructure. Generally, as hydrogen exposure conditions, like pressure and load intensity, become more demanding, higher-quality materials are required, which are typically associated with increased material costs. For austenitic stainless steels, the nickel equivalent serves as an important indicator of hydrogen resistance. Higher nickel equivalents in standard austenitic stainless steels generally correlate with improved resistance to hydrogen embrittlement, although there are exceptions to this rule. Various formulas exist to calculate the nickel equivalent, each adapted to specific compositional or environmental requirements.

To evaluate the hydrogen resistance of austenitic stainless steels, Slow Strain Rate Testing (SSRT) is commonly used. A case study demonstrated that the DMV 316L MoS alloy, with its higher nickel equivalent, exhibits superior hydrogen resistance compared to standard 316L under high-pressure conditions. Nonetheless, both DMV 316L and DMV 316LMoS steels show high hydrogen resistance overall. In addition to technical considerations, cost factors must also be considered in material selection, as austenitic stainless steels with higher nickel equivalents are generally have increased costs.

Sources

- J. Venezuela, Q. Liu, M. Zhang, Q. Zhou, A. Atrens: A review of hydrogen embrittlement of martensitic advanced high-strength steels, Corrosion Reviews 34 (2016)

- T. Freitas, F. Konert: Tensile testing in high-pressure gaseous hydrogen using the hollow specimen method, MRS Bulletin, Volume 49 (2024)

- B. Abebe, E. Altuncu: A Review on hydrogen embrittlement behavior of steel structures and measurement methods, International Advanced Researches and Engineering Journal Volume 8 (2024)

- A. Trautmann: Wasserstoffversprödung von Werkstoffen bei der Erzeugung erneuerbarer Energien, Dissertation at the Chair of General and Analytical Chemistry at the Montan University Leoben (2020)

- M. Hatano, K. Matomoto, M. Sugeoi, K. Hattori: Development of austenitic Steel with reduced amount of nickel and molybdenum for hydrogen use, Nippon Steel technical report No. 126 (2021)

About the author

Tim Wallbaum is the R&D and Sustainability Manager for the DMV GmbH in Mülheim, Germany. Tim has a Master of Science in Mechanical Engineering and as a young engineer and manager, is keen to make a contribution to sustainable steel production and processing.

Tim Wallbaum is the R&D and Sustainability Manager for the DMV GmbH in Mülheim, Germany. Tim has a Master of Science in Mechanical Engineering and as a young engineer and manager, is keen to make a contribution to sustainable steel production and processing.

About this Tech Article

Appearing in the November 2025 issue of Stainless Steel World Magazine, this technical article is just one of many insightful articles we publish. Subscribe today to receive 10 issues a year, available monthly in print and digital formats. – SUBSCRIPTIONS TO OUR DIGITAL VERSION ARE NOW FREE.

Every week we share a new technical articles with our Stainless Steel community. Join us and let’s share your technical articles on Stainless Steel World online and in print.