Keeping the electricity grid up and running through summer heat waves and winter deep freezes is an ongoing balancing act. Power lines that stretch for miles are vulnerable to wind and fire. Surges in demand for heating and cooling strain capacity, which can lead to blackouts. Air pollution is an ongoing issue. Although meeting today’s energy needs requires the use of traditional hydrocarbon fuel sources, alternative-energy solutions such as solar, wind-power, and hydrogen are rising up in the supply curve as the drive to decarbonize electricity gains momentum. Of these, hydrogen stands out, given its potential to produce clean electricity at a steady rate.

By Lynn Manning, President, Parker Group

A promising approach, now emerging from the research stage into commercialization, is solid-oxide fuel cell (SOFC) technology. The US Department of Energy (DOE) has invested in SOFCs for years (USD 750 million since 1995, according to their website) as part of the ongoing effort to decarbonize energy production.

The DOE describes an SOFC as an electrochemical device that produces electricity directly from the oxidation of hydrogen, generally produced by reformation of a hydrocarbon fuel (usually natural gas), while eliminating the actual combustion step. Basically, an SOFC acts like an infinite-life battery that is constantly being recharged – without burning the gas that recharges it.

Small package, big energy output

“Solid oxide fuel cells are very attractive because they produce a lot of energy in very small packages,” says Jose Luis Cordova, Ph.D., VP of Engineering at Mohawk Innovative Technology Inc. (MITI). Working on a number of DOE-funded programs, Mohawk is a 28-year-old, Albany, New York-based company specializing in the design of high-efficiency, cost-effective, environmentally low-impact, oil-free turbomachinery products including renewable energy turbogenerators, oil-free turbocompressors/blowers, and electric motors.

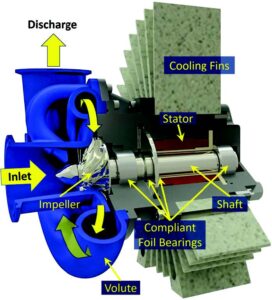

“SOFCs are compact and can be built at a factory, then transported to the specific site where they’re needed to support distributed-energy production,” says Cordova. “Contrast that with the usual centralized, multimegawatt power plant that takes billions of dollars and many years to set up. SOFCs are also very efficient. Unlike a regular battery, they don’t lose power over time because as long as you supply the reagents you can continue the electrochemical reactions pretty much indefinitely.” Sounds ideal, and more than 40,000 units of 100-kilowatt fuel cells (each able to power 50 homes) were View of an oil-free anode offgas recycle blower (AORB) made by Mohawk Innovative Technology Inc.

shipped worldwide in 2019. But there have been bumps in the road slowing more widespread adoption of the technology: many SOFC components are expensive to manufacture and, due to exposure to the very gases that make their operation so efficient, they wear out frustratingly quickly.

Facing cost and durability issues

To help overcome such challenges, Mohawk has designed some of those critical parts for longer lives and greater efficiency. One example is the anode offgas recycle blower (AORB), an essential component of the ‘balance of plant’ – the machinery that supports the SOFC’s fuel stack. During operation, each fuel cell only uses about 70% of the gas it’s fed; some 30% passes right through the system along with water (a product of the electrochemical reaction). “You don’t want to throw away the leftover gas or water, you want to send them back to the beginning of the process,” says Cordova. “And that’s where the AORB comes in; it’s essentially a low-pressure compressor or fan that recycles the exhaust and returns it to the front of the fuel cell.”

“SOFC balance-of-plant designers were thinking that this blower would be an off-the-shelf unit,” says Cordova (a typical 250 kW SOFC plant would employ two of them). “But due to the process gases in the system, traditional blowers tend to corrode and degrade; the hydrogen in the mixture attacks the alloys the blowers are made of and also damages the magnets and electrical components of the motors that power the blowers. Most blowers also contain lubricants, like oil, that degrade as well. So you end up with very low-reliability blowers – representing a significant portion of the balance-of-plant cost – and your SOFC plant needs an overhaul every two to four thousand hours.”

This statistic falls far short of the DOE’s goal of an operating lifetime of 40,000 hours for a typical SOFC – as well as an installation-cost reduction from an average of USD 12,000/kWe (kilowatt of electrical energy) to USD 900/kWe.

Time to rethink those blowers! “So we realized that Mohawk’s proprietary, oil-free, compliant foil bearing (CFB) technology, specialized coatings, and decades of turbomachinery expertise were a good fit for this challenge,” says Cordova.

| Quantity | Method | Blade # | Unit Cost USD |

| 1 or 2 | 5 axis machining | 19 | $ 18,950 |

| 1 or 2 | 5 axis machining | 15 | $ 15,845 |

| 5 to 10 | Investment casting | 15 or 19 | $ 3,800 to $ 1,900 |

| 2 | LPBF-3D Printing | 15 or 19 | $ 1,005 |

| 12 | LPBF-3D Printing | 15 or 19 | $ 614 |

Additive manufacturing offers answers

DOE funding provided the means for Mohawk to design and test AORB prototypes in a demonstrator SOFC power plant run by FuelCell Energy. Rigorous testing under realistic operating conditions measured durability and performance, with the latest versions demonstrating no significant degradation in parts or output and complete elimination of any performance or reliability issues. Yet the cost of an AORB remained prohibitively high – in large part due to its high-speed centrifugal impeller, which operates continuously under extreme mechanical and thermal stress. For longest life, this part must be made from expensive, high-strength, nickel-based, corrosion-resistant superalloy materials like Inconel 718 or Haynes 282 that are difficult to machine or cast. In addition, achieving optimal aerodynamic efficiency in an impeller requires complex three-dimensional geometries that are a challenge to manufacture. And because of the incipient nature of the current SOFC market, impellers are produced in relatively small batches, and economies of scale are difficult to realize.

How to bring that cost down? Additive manufacturing (AM, aka 3D printing) provided a compelling answer. While the original project with FuelCell Energy was evolving, Mohawk was also getting calls from R&D groups looking for help with their own fuel-cell component designs. “Because many of these manufacturers and integrators were still at the research stage, each one had a different operating condition in mind,” says Cordova. “Using traditional manufacturing, to make just the handful of the custom impeller wheels or volutes they wanted, would have been extremely expensive. So that’s where we started looking at AM; we did our own research into AM system makers and connected with laser-powder-bed fusion (LPBF) provider Velo3D.”

Collaborating on capabilities

With its goal of reducing costs and improving performance of SOFCs, the DOE is enthusiastic about innovative manufacturing methods such as AM, says Cordova. “Their funding [through The Small Business Industrial Research Project] supports our current partnership with Velo3D as well as our previous one with FuelCell Energy. An additional benefit is that this work is helping advance 3D printing technology in general

as we learn more and more about its capabilities and potential.”

Velo3D’s Mohawk-project leader Matt Karesh agrees. “Working hand in hand with companies like Mohawk, who are willing to collaborate with us and give us feedback, drives progress on our internal process parameters and capabilities, and helps direct us as to how to make our print methodologies better,” he says.

A nice price surprise

The switch to AM was an eye-opener: “Our traditional, subtractively manufactured impeller wheels were running up to $15,000 to $19,000 apiece,” says Cordova. “When we 3D printed them, in small batches of around eight units rather than one at a time, this dropped to $500 to $600 – a very significant cost reduction.

“As well as cutting manufacturing costs, LPBF is the one technology that could provide us with the design flexibility we were looking for. AM is indifferent to the number of impeller blades, their angles, or spacing – all of which have a direct impact on aerodynamic efficiency. We now have the geometric precision needed to achieve both higher-performance rotating turbomachinery designs and reduce associated manufacturing costs.”

Picking the perfect alloy

For 3D printing impellers on a Velo3D Sapphire system (at Duncan Machine, a contract manufacturer in Velo3D’s global network), the choice was made to use Inconel 718 – one of the nickel-based alloys with a strong temperature tolerance that withstand the stress of rotation best.

“Inconel was very attractive to us because it’s chemically inert enough and retains its mechanical properties at pretty high temperatures that definitely surpass aluminum or titanium,” says Mohawk mechanical engineer Hannah Lea.

Although Velo3D had already certified Inconel 718 for their machines, Mohawk did additional material studies to add to the body of knowledge about the 3D-printed version of the superalloy. “Our tests demonstrated that LPBF 3D-printed Inconel 718 had mechanical properties, like yield stress and creep tolerance, that were higher than those of cast material,” Lea says. “This was more than adequate for high-stress centrifugal blower and compressor applications within the operational temperature range.”

Iteration made easy

As their impeller work progressed, Mohawk’s engineers collaborated with Velo3D experts on design iterations, modifications and printing strategies. “It was really interesting because we didn’t have to make any major design changes to the original impeller we were working with – with Velo3D’s Sapphire system we could just print what we wanted,” says Cordova. “We did do some process adjustments and tweaking in terms of support-structure considerations and surface-finish modifications.”

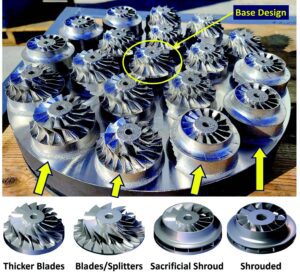

Of course, tweaking is just another day in the office for design engineers. As the impeller project progressed, AM provided much faster turnaround times than casting or milling would have allowed, since parts could be printed, evaluated, iterated and printed again quickly. In subsequent 3D printing runs, multiple examples of old and new impeller designs could be simultaneously made on the same build plate to compare results.

The relatively small size of the impellers (60 millimeters in diameter) necessitated the team’s development of a ‘sacrificial shroud’ – a temporary printed enclosure that held the blades true during manufacturing.

Sacrificial shrouds and smoother surfaces

“What was really interesting about this approach is that shrouded impellers are, for most current additive technology, basically untouchable because of all the traditional support structures they require,” says Velo3D’s Karesh. “We used a, not support-free, but reduced-support approach. Mohawk was saying, ‘we don’t need the shroud in the end, but the shroud makes our part better, so we’ll attach this thing that’s typically extremely hard to print – and just cut it off after.’ Using Velo3D’s technology, they were able to build that disposable shroud onto their impeller, get the airfoil and flow-path shapes they wanted, and then it was a very simple machining operation to remove the shroud.” Surface finish was another focus, as Mohawk engineer Rochelle Wooding explains: “The surface was a bit rough in our early iterations. What was interesting about the sacrificial shroud was that it gave us a flow path through the blades that we could use to correct for roughness using extrusion honing; it took some further iteration to determine how much material to add to the blades to achieve the required blade thickness that we wanted. The final surface finish we achieved is comparable to that of a cast part and suits our purposes aerodynamically.” What’s more, all critical design dimensions enabling proper impeller operation were within tolerances.

Future testing, forward outlook

Next steps are retrofitting AORBs with the new impellers and testing them in field conditions. “We expect that successful execution of these two tasks will fully demonstrate that 3D-printed Inconel parts delivered by LPBF technology are a viable and reliable alternative for manufacturing turbomachinery components,” says Cordova. Work is already underway using AM for other blower parts like housings and volutes.

Cordova is particularly proud of the professional credentials and work ethic of the two young women engineers who’ve been engaged in these recent in-house projects. “I never really feel like I have an easy day here,” Wooding says. “But I really enjoy that!”

She’s also keenly aware of the greater value of what they are doing: “Through these DOE-funded projects we’ve been able to develop a library of common parts. Based on the original idea, we now have at least three completely different platforms that can serve different power capabilities to support progress for the clean energy of the future.”